News – 2017

This page reproduces CHG-related articles published in local newspapers etc.

Our Chairman, Alan Brunton, writes a regular (generally fortnightly) short article on various aspects of our local history which are published in the Mid Devon Advertiser (MDA). This page reproduces some of Alan's articles published earlier this year. They are mostly based on information contained in The Chudleigh Book (and related Year Books published by CHG, plus articles on this website), but often cut across more than one headline topic and so give a different and personal spin on the original – and more formal – presentations. Articles are posted here in order latest first to oldest last; new ones should appear (approximately) every two weeks, a week or so after MDA publication.

The Earl of Harcombe (Pt.2) – The Earl of Harcombe – Castle Dyke – Harcombe – Kerswell & Harcombe – Knights of the Road

The Earl of Harcombe (Part 2)

During his incumbency as vicar of St Martin and St Mary church in Chudleigh between 1970 and 1998, Christopher Pidsley came to know Vic, a tramp locally referred to as the Earl of Harcombe, who spent much of his time in the town and used an old lime kiln in the north of the parish as his place of rest. In my last article I wrote of how Christopher helped Vic following his plea one day to 'trying to find out who I am'. Having been torpedoed twice during the Second World War whilst serving in the merchant navy, these experiences had left him mentally scarred. Christopher helped in fulfilling his plea and in this article I'll reflect of his personal memories of the Earl of Harcombe.

Christopher made it a rule that he never gave money to those who came to the vicarage door. Vic was the exception and on two occasions it was a point of honour to repay a loan. He was taken ill and Christopher took him to Bovey Tracey Hospital where they found he was suffering from pneumonia. Upon visiting him a few days later Vic said he wished to reimburse him for his petrol expenses. On another occasion Vic caught the train to Manchester and then realised he did not have enough money to purchase a return ticket. He called in to the Church of Holy Trinity in Rusholme and asked the curate to phone Christopher, stating if the curate would lend him the £23 for a return ticket, Christopher would send the money to repay him. This Christopher did and a few days later Vic was on the vicarage doorstep looking clean and tidy, wearing a replacement mackintosh and a smart pair of suede shoes from the Methodist Church, and the first instalment of £5 to repay his debt. Having been in the merchant navy he was entitled to a naval pension.

During the 1980s he would travel north for the summer. Before he left he would bring what he described as his valuables to the vicarage for Christopher to look after. Packed in a battered suitcase was a motley collection of items consisting of pots and pans, a teapot and an old blow lamp which he described as 'a real antique you know'. The vicarage during the following weeks would receive postcards from visits to Blackpool, several of which Christopher still has, and the occasional phone call 'just to let you know I am alright'.

Despite his often fearsome appearance Vic had a kind heart. One year just after Christmas he was anxious to know if Christopher and his family had found 'the presents for the children' which he had left in the hedge near the vicarage front door. A bag was subsequently found containing two children's books, a sprig of holly and twelve pence. One Christmas he accepted the family's invitation to Christmas dinner which he insisted eating in the conservatory. The following year he was invited again but he declined as he had already planned to have duck, so Anne, Christopher's wife, gave him some mince pies for dessert. A few days later Anne asked him how his Christmas duck went down to which he replied 'it was a wild duck and flew away'.

During the autumn of 1988 Christopher became concerned over Vic's wellbeing as he had not seen him for a few weeks, and he always let him know if he was going away. The lime kiln was empty and the fire embers cold and Christopher learned Vic had been taken to Heavitree Hospital. Once discharged he was placed in the care of a Mrs Saunders in Mount Pleasant, Exeter. She was a kindly lady who was also looking after two other men in similar circumstances. Christopher recalls taking him some pyjamas, something he had not worn for many years. At last he had managed to settle, enjoying warmth and comfort and sustained by regular meals – no more wild duck. However, there was to be no return to his lime kiln.

Vic died on 31st October 1990 aged 73. His funeral, which Christopher took at Exeter Crematorium a week or so later, was attended by a few Chudleigh residents and his ashes interred in Chudleigh churchyard. On the official papers his name was recorded as Frank Robin Victor Whitton. Who knows whether these names described his true identity. At least he died knowing key parts of his life story. He was a man who at long term personal cost had played his part in helping to sustain our nation in the dark days of war. To Christopher he became a true friend and one he remembers with great affection.

Many years ago he recalls hearing a radio broadcast under the title 'What Life has taught me' featuring George Thomas, a Welsh MP who became a Speaker of the House of Commons. During the broadcast he said in his lovely Welsh accent 'I have discovered that with God, there are no unimportant people'. Christopher reflects it was a lesson for him reinforced through his friendship with Vic and one it would do us all well to remember.

Christopher Pidsley far right, vicar of St Martin and St Mary Church

at the opening of the new school in 1992

This article will be my last for a while – I'm running out of subject matter. I would like to submit a few more as we near the centenary of the closure of the First World War next year.

Alan Brunton

(

The Earl of Harcombe

Several weeks ago I wrote an article headed Knights of the Road and briefly mentioned a tramp known locally as Old Vic, who used a disused lime kiln between the carriageways of the A38 on the Harcombe bends as a resting place. He was referred to as the Earl of Harcombe and the lime kiln as The Flats. Recently myself and Christopher Pidsley, who was the vicar of our church St Martin and St Mary between 1970–1998, have given two presentations to History Group members and Chudleigh residents during Carnival week, entitled Anecdotes from Chudleigh's Past during which Old Vic was mentioned. Unbeknown to me, Christopher had got to know Vic quite well whilst the vicar here and had completed a record of his findings from which the following article is compiled.

Upon his arrival as 'the new young vicar' Christopher soon became aware of a familiar figure in the town usually wearing an old raincoat tied about his waist with string, and riding or more often pushing a very old and dilapidated bicycle. His weather beaten face was framed by an unkept beard and wild eyes peered from beneath bushy eyebrows. He had a selection of old hats and if it was wet would wear a plastic bag with the corners turned up which resembled a Viking helmet. Cider was his preferred drink and having satisfied his thirst would rest in the town centre shouting incoherently at passers by, and to many, especially the children, he was a rather fearsome figure.

Soon after Christopher and his family had moved into the vicarage, Vic became a frequent visitor and Christopher's wife Anne, who was wonderfully patient with him, often made him a cup of tea and a cheese sandwich. Another of his port of calls for the occasional hot meal was the convent up Heathfieldlake Hill, a closed community of Redemptoristine Nuns, where dinner was passed out through a rotating hatch without any visual contact. On a Sunday morning he would often arrive after morning service in the church, knowing he would receive a kindly welcome and a cup of coffee and biscuits.

Christopher recalls a particular poignant moment when one day Vic said to him 'I have spent all these years trying to find out who I am'. His earliest memory was of playing musical chairs with an older sister and later of being a small child in a house in Ireland that had a large garden and a summer house, in which he sometimes slept. One day he crept through a hole in the hedge and was picked up by gypsies from a visiting fair and taken away in a donkey cart with a high tailboard. He thought he had been kidnapped. Christopher found his story hard to believe and yet parts of it gave it a ring of authenticity. On another occasion Vic said he was placed with foster parents in Salford and remembered their names. His foster father was in the Greater Manchester Police and he also recalled singing in the choir of the Church of St John the Evangelist. For Christopher this information was something he could follow up and in so doing the name of his father was confirmed as having been in the police between 1909–1931 and that the church was within walking distance of the foster parents' address.

Vic remembered his foster mother being killed in a tram accident, the same day Sir Henry Seagrave died attempting to break the world water speed record. This also checked out as being correct during June 1930. He left school aged 14 and went to work on a farm owned by a Mr Hargreaves. A few years later he joined the Merchant Navy as a stoker and suffered permanent damage to his sight during a dispute amongst the crew. During the Second World War he served on ships which were part of the Atlantic Convoys, bringing food supplies and armaments to the United Kingdom. Twice he was torpedoed and rescued, but these traumatic experiences left him with mental scars.

These recollections made Christopher want to help Vic even more and when Chudleigh residents complained about his presence in the town, he quietly shared some of this information. Attitudes and forbearance soon changed.

The Merchant Naval ships that Vic did service on during the war operated from the Barry Dock in South Wales. He remembered his seaman's number as R16129 and recalled lodging with two ladies when ashore, but unfortunately enquiries to the British Sailor's Society drew a blank.

In my next article I'll write of some of Christopher's personal memories of this old Chudleigh character.

Alan Brunton

(

Castle Dyke

Castle Dyke is on the ridge overlooking Chudleigh on the eastern side. It lies within Ugbrooke Park.

Until the 20th century historians gathered most of their information from stories, beliefs and the few written records passed down over the years. Since then technology has revealed that acceptance of those beliefs has sometimes been far removed from the reality. In Mary Jones' title The History of Chudleigh, published in 1852, of which I have referred to in previous articles, she was incorrect in stating that Castle Dyke was a Danish circular encampment. She presumed it was constructed in the 9th century following the Danes ransacking and burning Teignmouth. It is in fact an Iron Age hillfort which would have been a Bronze Age settlement before that. It is over 4,000 years old. Just when it became known as Castle Dyke I do not know but the Ordnance Survey maps show it as such and several other publications, such as Aileen Fox's Prehistoric Hillforts in Devon, published in 1996, lists it similarly.

There are several definitions of the word Dyke in the dictionary; a long wall or embankment to prevent flooding, an earthwork serving as a boundary or defence, a causeway and a ditch or watercourse. Chudleigh's Castle Dyke is certainly an embankment and an earthwork. The only similarity it has to a castle is that it occupies a very high prominent position as do so many other castles. [Many such hillforts are called 'castle', e.g. Maiden Castle in Dorset – Ed.]

Only parts of the embankment can be seen from the ridge road that leads to Gappah and is best seen in the winter months when the trees and bushes are not in leaf. The oval shaped hillfort enclosure is surrounded by this substantial rampart and ditch which were constructed to keep stock in as well as a defence from attack. It is situated on the summit of a 140 metre hill and measures 300 metres in length and 200 metres width. There are exits/entrances at either end, north-west and south-west. Any evidence of a Bronze Age settlement has been lost under the Iron Age occupation.

Hillfort sites were chosen for their natural defence of seeing a potential invasion miles away. They were generally associated with the surrounding farming community who in times of trouble would seek protection from within the hillfort ramparts.

Castle Dyke bank & ditch (1965)

The late Roger Brandon wrote the chapter headed The Emergence of a Settlement in the 2009 publication The Chudleigh Book and he wrote that the occupiers of the hillfort were part of the Celtic Dumnonii tribe who controlled the southwest peninsula. They suffered little from insurgents and were generally hospitable and friendly towards strangers. In any case foreign invaders had little interest in exploring the wild lands of the southwest until the Romans came.

There is no evidence of Roman presence in Chudleigh apart from a few coins found near Rock Road, which only shows they were in circulation throughout the area. Of interest is that on the Ordnance Survey map of Roman Britain it shows a road through the parish on the eastern side. From Exeter it more or less followed the line of the existing A380 to Thorns Cross before passing through Wapperwell and Ugbrooke Park then to Hackney Marsh and onto Totnes. Perhaps the hillfort, only a few hundred metres from the Roman road, did attract some Roman attention, if only to keep an eye on the town below.

Several years ago a local Archaeological Dowser's group, upon the invitation of Lord Clifford, carried out extensive surveys of the area around Castle Dyke and Ugbrooke House using techniques similar to water dowsing. From their findings they have drawn up plans of a Roman fortress which they believe was in existence during the Roman occupation. No geophysics, archaeological dig or other evidence supports these beliefs and conventional archaeologists would no doubt question their findings.

Alan Brunton

(

The Hamlet of Harcombe

This hamlet lies to the north of the parish above a sheltered valley that runs northeast from the Haldon Hills towards the River Teign. For a good way it plays host to the Kate Brook.

During the latter half of the 19th century there were at least a dozen cottages, a small infants' school and a cottage Sunday service in the hamlet. In 1870 the schoolmistress was Mrs Elizabeth Endicott. Records show the hamlet being in existence from the 16th century.

During the 17th century Harcombe was owned by the Balle family who at that time owned other parts of the parish including Wapperwell, Bridgelands, Ranscombe and Northwood. Two mills operated alongside the Kate Brook below the now present Harcombe House; the remains of one can still be seen.

An 1890 Ordnance Survey map shows cottages on the lower slopes of Haldon above what is now the holiday bungalow park. It is now scrub and woodland and several years ago History Group member Des Shears and myself explored the parish boundary which passes through this woodland and found the remains of what we believe to have been the most northerly dwelling of the parish. There is also mention of Harcombe cottages in the 1901 census.

The hamlet became deserted and cottages destroyed in the early 20th century when Sir Edward Chaning Wills purchased the Harcombe Estate and started building Harcombe House. The cottages would have been too close to the house for privacy and much of their stone was used in the building of the new property.

The newly-built Harcombe House in late 1912 or early 1913

The aforementioned Balle family's wealth was acquired from fishing and wine. They owned a fishing fleet which worked out of Brixham and fished the cod waters around the coast of Newfoundland. Upon leaving Brixham they often sailed to Portugal to pick up the wine before heading across the Atlantic to the fishing grounds. The wine would have been left in Newfoundland to mature before bringing it back on subsequent trips. Sometimes the catch would have been salted down and taken to Portugal before returning with the wine. This was quite a lucrative business but a precarious way to earn a living. In 1751 over 100 ships from various fleets along the south coast were lost. Readers will recall I wrote about this trade several weeks ago and mentioned that the village of Shaldon was built on the profits from this industry.

The Balles were obviously well respected and held a degree of influence in parish matters. They were Overseers of the Poor in Chudleigh. Some of the family are buried within the parish church. An inscribed stone to John Balle, his son also named John and daughter Sabrina – who all died between 1656 and 1669 – is under the carpet in the south aisle.

The Chudleigh Balles were closely related to the Balle family in Mamhead. Giles Balle purchased the Mamhead Manor around 1580 and it was his son Peter who built Mamhead Castle. During the 1740s another family member, Thomas Balle, built the Mamhead Obelisk, believed to be as a landmark for ships coming up the English Channel to the Exe Estuary. The family at this time held Higher Harcombe, Mamhead and Ashcombe.

In 1823 Thomas Newman, of the Dartmouth wine merchants family, purchased them and so began the development of Harcombe. His son Robert took a great interest in improving Harcombe but was killed at the Battle of Inkerman during the Crimean War in 1854. The Newmans bought the farmhouse and land of Lower Harcombe from the Earl of Morley, of Whiteway, in 1830. The Whiteway Estate adjoined Lower Harcombe and the Earl retained ownership of several cottages in the hamlet for Whiteway employees.

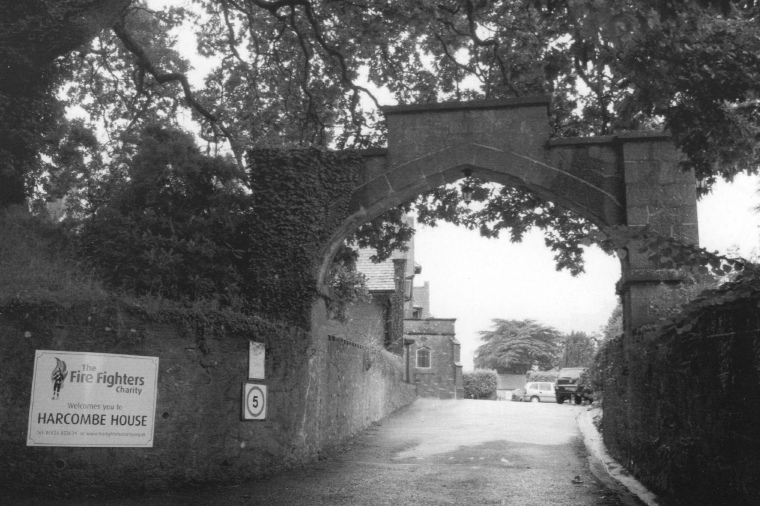

Chaning Wills died in 1921 shortly after the completion of building Harcombe House, but his widow Lady Isabella Wills survived her husband by thirty-two years. Since then the house and estate has endured several owners and is now owned by the Fire Fighter's Charity, previously known as The Fire Services National Benevolent Fund (FSNBF). An example of conforming to 21st century standards of the English language which we are now subjected to.

Entrance to Harcombe House. The inscrption in the centre of the arch is '1912'

Alan Brunton

(

The Hamlets of Kerswell and Harcombe

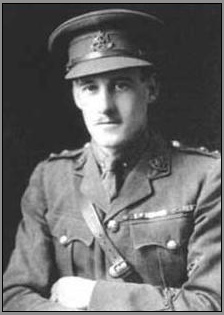

Having written about Upcott and Waddon in my last article, today we look at two other hamlets in the parish of Chudleigh. Approaching Kerswell along the minor road from Hams Barton a large whitewashed detached house can be seen across the fields to the right. This is Kerswell House and stands in a limestone quarry basin. The original house, which was burnt down in the late 1940s, was built in the late 19th century. Before its demise it was the home of Brigadier Charles Edward Hudson.

Hams Barton. The lane behind us leads to Kerswell

Born in Surrey in 1892 Hudson completed his schooling at Sherborne School in Dorset and then went to the Royal Military College in Sandhurst before, in 1912, going to Ceylon to work as a tea planter and serving in the Ceylon Mounted Rifles. Upon the outbreak of the First World War he returned to England and was granted a commission in the Sherwood Foresters with whom he served in France and Italy. During this time he received several military honours and in 1918 was awarded the Victoria Cross. His military career saw him in active service on the Western Front in 1941 during the Second World War and from 1942, until his retirement in 1946, he was Aide-de-camp to the King. Following the fire at Kerswell House the Hudsons moved to the Manor House in Denbury. He died whilst on holiday in the Scilly Isles in April 1959 and is buried in the Denbury churchyard.

Brig. C.E. Hudson VC (1892–1959) of Kerswell House

Of historical interest, at the driveway entrance to the present Kerswell House there is a postbox from Queen Victoria's reign. It is clearly marked VR (Victoria Regina) and although well over 100 years old is still in current use. Just past the driveway is a fine example of a block of open fronted limekilns. To the passer-by they look like small caves which are now used as storage facilities. Immediately alongside, but hidden by undergrowth, are the remains of the limeburner's cottage, a few yards up the footpath alongside Kerswell Cottage. These kilns are from the 17th century and would have had the limestone tipped into them from above. The shafts are now capped and no longer visible. The kilns would have been stacked with brushwood, kindling and coal if available and set alight. The molten limestone would have been drawn off from the draw hole and if wanted for fertiliser, allowed to cool and then crushed into granules. If wanted as limewash or mortar, water would be added to obtain the liquid required.

Behind the limekilns and on private land lies another large disused quarry basin. Before the Second World War and used by the Hudsons, it accommodated tennis courts and a pavilion; the remains of the latter could still be seen when I was shown around a few years ago by the owner of Kerswell House. Mary Jones in her History of Chudleigh published in 1852, tells us that during the mid 19th century, Kerswell was owned by a Mr Richards who had purchased it from Lawrence Palk, the owner of Haldon House. Apparently the public had access to the top of Kerswell Rock and admired the views it offered over the Teign Valley and Dartmoor beyond. Mr Richards constructed the road which leads from Kerswell to Haldon via Sticks End cottages and Harcombe. Part of this would have been the road Sir Chaning Wills closed when he purchased the Harcombe Estate in 1912. Following complaints, the then Chudleigh Town Council asked for advice from the Newton Abbot Rural District Council who declared the road a public highway and told Chaning Wills to remove the gates he had installed forthwith. The council minutes say the matter was settled amicably but this was not the case. From that day on and until his death in 1921, Chaning Wills refused to employ anyone who lived in the Chudleigh parish.

In my next article I'll write more on the hamlet of Harcombe.

Alan Brunton

(

Knights of the Road

Now completely overgrown and out of sight, between the north and south bound carriageways of the A38 at what we refer to as the Harcombe Bends, lies a fairly large old lime kiln. During the latter half of the last century this and another nearby were referred to as the Harcombe Flats, and more locally as Ivy's Cottage, being the occasional resting place for those who preferred a nomadic way of life, divorced from most people's traditional work, rest and play. Several of these gentlemen and at least one lady used these redundant lime kilns and earned quite a reputation in Chudleigh.

Local resident and History Group member Des Shears, of whom I have previously mentioned, remembers Ethel, one of the local tramps. He believes she was married at one time and may have been the Mrs Ryder whom Chips Barber mentions in his title Around & About the Haldon Hills, published in 1982. Now retired, Des used to be the local plumber and was frequently called out to properties in the parish to undertake plumbing repairs. He often spotted Ethel who seemed to spend much time roaming the local lanes and outlying farmsteads and who as Des says 'could somehow sense where and when a meal was in the offing and using the old adage of beg steal or borrow, she rarely went without a repast of some description'. One instance he recalls vividly was when he left his van in the driveway to a large house whilst carrying out some work within. Glancing at his van he noticed Ethel in the vicinity and not being particularly concerned thought little of it, until looking for his lunchbox two hours later. It should have been on the passenger seat but was nowhere to be found, then the penny dropped – Ethel had made off with it! Relating this story later in the day to a work colleague Des was told this was typical of Ethel, finding the whereabouts of local tradesmen and pinching what she could find in a parked vehicle, which more often than not was unlocked. Des added she was as hard as nails, with the constitution of an ox. Even on a cold winter's night if she thought the walk back to Ivy's Cottage was too far, she simply slept under the stars. One day she just went missing and was never seen in the locality again, but she was certainly one of Chudleigh's characters.

Another knight of the road who frequented the Flats was Vic, a familiar sight with his bicycle who was around for many years during the 1970s and 80s. He was nicknamed locally as the Earl of Harcombe. Apparently he was an old naval man and one whom our previous vicar, Christopher Pidsley, came to know quite well. Being entitled to a naval pension, Vic would cycle, or more often push, his bike into town to collect it on a regular basis and then visit one or two other establishments to buy essentials. Hygiene not being of particular importance to him guaranteed him prompt service and he emptied shops quicker than a bomb alert. Vic passed away nearly twenty-five years ago.

When I was writing a book on local walks many years ago I mentioned the Harcombe Flats. At that time the lime kiln was not so concealed as now and early one morning with little traffic around, I went and had a look for myself and took some photographs. Obviously vacated a few years earlier the kiln still accommodated some old bedding, chairs and a grill over what would have been an open fire.

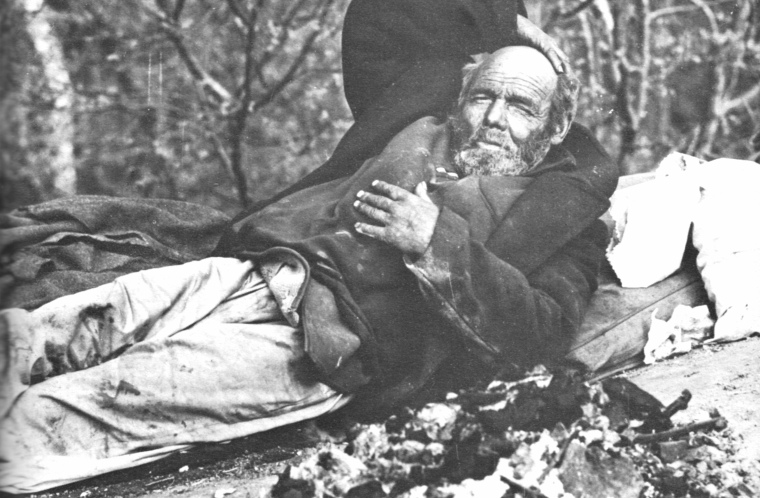

Many residents will remember Smokey Joe. For many years he lived in a small cave adjacent to the A30 in Cornwall before moving on and settling in a ramshackle hut of sorts in woodland alongside the brow of Telegraph Hill, on the Torbay bound carriageway of the A380. This was during the early 1970s. He gained his name because of the colour of his features, probably gained from the continuous smoke from his fire and lack of soap, rather than spending twenty-four hours a day in the open air. He became a living landmark to passing motorists who often slowed down when approaching his whereabouts to hurl a variety of goodies in his direction. During 1975 his rugged and self imposed lifestyle caught up with him and following calls from concerned motorists, who had not seen him for several days, the police found him in a distressed condition and he was admitted to the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. He was a very ill man and although a prolonged hospital stay allowed him some comfort he passed away in January 1976. Upon hearing of his demise several locals placed a floral tribute at his location on Telegraph Hill which prevailed for several months.

'Smokey Joe'

[photo by Nicholas Toyne from 'Around & about the Haldon Hills' by

Chips Barber (1982)]

Nowadays we seldom see any of these knights of the road but last year I met one on the coastal path behind the Fleet nature reserve near Weymouth. Wearing a long grubby raincoat and carrying a large bin liner on his back and sporting a shaggy beard, he was walking westwards. We exchanged a few words and then went on our ways. Two weeks later I was driving from Dawlish Warren to Cockwood Bridge and passed him again. I tooted the horn and gave him a cheery wave to which he responded obviously not having any idea that we had met previously. I wonder if he is still walking.

Alan Brunton

(